By Joy DeLyria and Sean Michael Robinson

There are few works of greater scope or structural genius than the series of fiction pieces by Horatio Bucklesby Ogden, collectively known as The Wire; yet for the most part, this Victorian masterpiece has been forgotten and ignored by scholars and popular culture alike. Like his contemporary Charles Dickens, Ogden has, due to the rough and at times lurid nature of his material, been dismissed as a hack, despite significant endorsements of literary critics of the nineteenth century. Unlike the corpus of Dickens, The Wire failed to reach the critical mass of readers necessary to sustain interest over time, and thus runs the risk of falling into the obscurity of academia. We come to you today to right that gross literary injustice.

The Wire began syndication in 1846, and was published in 60 installments over the course of six years. Each installment was 30 pages, featuring covers and illustrations by Baxter “Bubz” Black, and selling for one shilling each. After the final installment, The Wire became available in a five volume set, departing from the traditional three.

Bucklesby Ogden himself has most often been compared to Charles Dickens. Both began as journalists, and then branched out with works such as Pickwick Papers and The Corner. While Dickens found popularity and eventual fame in his successive work, Ogden took a darker path.

Dickens’ success for the most part lies in his mastery of the serial format. Other serialized authors were mainly writing episodic sketches linked together only loosely by plot, characters, and a uniformity of style. With Oliver Twist, only his second volume of work, Dickens began to define an altogether new type of novel, one that was more complex, more psychologically and metaphorically contiguous. Despite this, Dickens retained a heightened awareness of his method of publication. Each installment contained a series of elements engineered to give the reader the satisfaction of a complete arc, giving the reader the sense of an episode, complete with a beginning, middle, and end.

One might liken The Wire, however, to the novels of the former century that were single, complete works, and only later were adapted to serial format in order to make them affordable to the public. Yet, while cognizant of his predecessors, Ogden was not working in the paradigm of the eighteenth century. As a Victorian novelist, serialization was the format of choice for his publishers, but rather than providing the short burst of decisively circumscribed fiction so desired by his readership, his tangled narrative unspooled at a stately, at times seemingly glacial, pace. This method of story-telling redefined the novel in an altogether different way than both Victorian novelists and those who had come before.

The serial format did The Wire no favors at the time of its publication. Though critics lauded it, the general public found the initial installments slow and difficult to get into, while later installments required intimate knowledge of all the pieces which had come before. To consume this story in small bits doled out over an extended time is to view a pointillist painting by looking at the dots.

And yet, there is no other form in which The Wire could have been published other than the serial, for both economic and practical reasons. The volume set, at 3£, was an extraordinary expense, as opposed to a shilling per month over six years. Furthermore, while The Wire only truly received praise from scholars, it was produced for the masses, who would be more likely to browse a pamphlet than they would be to purchase a volume set.

Lastly, one might stand back from a pointillist work; whereas physically there is no other way to consume The Wire than piece by piece. To experience the story in its entirety, without breaks between sections, would be exhausting; one would perhaps miss the essence of what makes it great: the slow build of detail, the gradual and yet inevitable churning of this massive beast of a world.

The genius of The Wire lies in its sheer size and scope, its slow layering of complexity which could not have been achieved in any other way but the serial format. Dickens is often praised for his portrayal not merely of a set of characters and their lives, but of the setting as a character: the city itself an antagonist. Yet in The Wire, Bodymore is a far more intricate and compelling character than London in Dickens’ hands; The Wire portrays society to such a degree of realism and intricacy that A Tale of Two Cities—or any other story—can hardly compare.

That is not to say that one did not have an influence on the other. Oliver Twist is a searing treatment of the education system and treatment of children in Victorian society; meanwhile, The Wire’s portrayal of the Bodymore schools is a similar indictment, featuring Oliver-like orphans such as “Dookey” and the fatherless Michael, and criminal activity forced upon children with Fagin-like scheming. Yet while Ogden no doubt took a cue from Dickens in his choice to condemn the educational institution, The Wire builds from the simplicity of Oliver Twist, complicating the subject with a nuance and attention to detail that Dickens never achieved.

In fact, Dickens, in later novels—which incriminate fundamental social institutions such as government (Little Dorrit), the justice system (Bleak House), and social class (A Tale of Two Cities, among others)—seems to have been influenced by The Wire. This is evidenced by the increased complexity of Dickens’ novels, which, instead of following the rollicking adventures of one roguish but endearing protagonist, rather seek to build a complete picture of society. Instead of driving a linear plot forward, Dickens, in A Tale of Two Cities and Bleak House, seeks to unfold the narrative outward, gradually uncovering different aspects of a socially complex world.

While Dickens is lauded for these attempts, The Wire does the same thing, with less appeal to the masses and more skill. For one thing, The Wire’s treatment of the class system is far more nuanced than that of Dickens. Who could forget “Bubbles”—the lovable drifter, Stringer Bell—the bourgeois merchant with pretentions to aristocracy, or Bodie—who, despite lack of education or Victorian “good breeding”, is seen reading and enjoying the likes of Jane Austen? Yet these portrayals of the “criminal element” always maintain a certain realism. We never descend into the divisions of “loveable rogues” and truly evil villains of which Dickens makes such effective use. Odgen’s Bodie, an adult who uses children to perpetrate criminal activity, is not a caricature of an ethnic minority in the mode of Dickens’ Fagin the Jew.

In fact, none of The Wire’s villains have the unadulterated slimy repulsion of David Copperfield’s Uriah Heep, except for perhaps the journalist, Scott Templeton. The final installments of The Wire were sometimes criticized for devolving into Dickensian caricature in regards to the plots surrounding Templeton and The Bodymore Sun. (It is interesting to note first that Dickensian characterizations were Templeton’s number one crime, and second, that these critics of The Wire were for the most part journalists themselves.)

If at any time besides its treatment of Templeton The Wire flirts with caricature, it does so in the character of Omar Little. Yet no one would ever reduce such a monumental culmination of literary tradition, satire, and basic human desire for mythos as Omar Little by defining him as mere caricature. Little is not Dickensian. Nor is he a character in the style of Thackeray, Eliot, Trollope, or any of the most famous serialists. If he must be compared to characters in the Victorian times, he most closely resembles a creation of a Brontë; he could have come from Wuthering Heights.

The reason that Little so closely resembles a Brontë hero is of course that the estimable sisters were often not writing in the Victorian paradigm at all, but rather in the Gothic. Their heroes were Byronic, and Lord Byron himself took his cue from the ancient tradition of Romance, culminating in Spenser’s Faerie Queene, but originating even further back. Little would not be out of place in Faerie Queene, and even less so in Don Quixote: an errant knight wielding a sword, facing dragons, no man his master. The character builds on the tradition of the quintessential Robin Hood and borrows qualities from many of the great chivalric romances of previous centuries. Meanwhile there is an element of the fey, mirroring Robin Hood’s own predecessor—Goodfellow or Puck—and prefiguring later dashing, mysterious heroes who also play the part of the fop, as in The Scarlet Pimpernel.

As previously mentioned, Little also has the flavor of the Gothic: brooding, hell-bent on revenge. Indeed, there is a darkness to the character that would not suit Sir Gawain, but does not seem out of place in a Don Juan or Brontë’s Heathcliffe. Little is in fact an amalgamation of these traditions, an essential archetype.

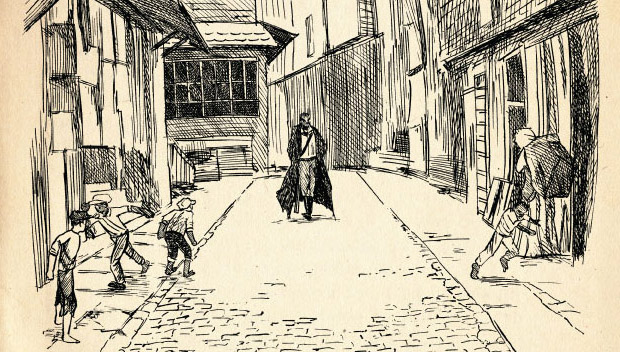

Yet, despite all this, Little can still not be called caricature. There is an awareness of literary canon in Omar Little, a certain level of dramatic irony. The street children and rabble, so Dickensian in their miscellany, always announce his presence, and even as The Wire grows and expands, so does the legend of Little. The Wire is aware of the mythic quality of its character, and allows the rest of the cast to observe it, indirectly commenting on the literary traditions from which Omar Little sprang. Only in the Victorian Age could Romanticism, Gothicism, and poignant satire come to a head in such a trenchant examination of the way such archetype endures. It is lamentable that our culture today, sorely devoid of new mythos, could not produce a character of such quality and social commentary.

Many characters of the age pale in comparison to The Wire, but if any other deserves explicit exploration, it is James “Jimmy” McNulty. While McNulty is rich in his own right, he is particularly interesting in comparison to the viewpoint characters of Dickens. As Dickens progressed from his “picaresque” adventure-style novels to his more serious explorations of society, so too did his central protagonist evolve. And yet, instead of gaining in complexity, Dickens’ viewpoint characters dwindled—in personality, idiosyncrasy, any unique or identifying traits.

Scholars believe the passivity of Dickens’ heroes was a direct result of his shift in style and subject matter: in order to portray the many aspects of society Dickens wished to explore, in order to maintain a strong supporting cast of highly individualized characters, he believed the main character must be de-individualized. He must become a receptacle of the injustices perpetrated by society, so that the failure of social institution can be witnessed and explored as the reader identifies with the protagonist’s essential powerlessness. This is an elegant method, used to near-perfection in David Copperfield, in which the only uninteresting character is David Copperfield himself.

The Wire charted another course. McNulty is a challenging character; in the beginning, he is not easy to like. Though he is our protagonist and usually our viewpoint character on our journey through The Wire, he begins and ends on a note that is extremely morally questionable, despite a redemptive arc mid-series. We are unable to approve of his actions, unable to assimilate his qualities as our own. Yet McNulty is powerless exactly in the way of David Copperfield. He is used and exploited by corrupt social systems, institutions, or figures of power in exactly the way of David Copperfield or Pip from Great Expectations. He is helpless to incite real and lasting change, his passivity forced upon him as he constantly struggles against it, rather than rising from an internal lack of agency. It is this very struggle which endears McNulty to us, in the end.

In fact, the number one way in which The Wire differs from any other Victorian novel is its bleak moral outlook. Dickens’ works almost always had a handful of characters that were essentially likeable. In the end, the power of love and truth is borne out and the individual triumphs over the ugliness of society by maintaining his integrity. Trollope, Eliot, Gaskell, etc all wrote with this essentially Western—not to mention imperialist—mind-set. Only William Makepeace Thackeray, in Vanity Fair—subtitled, A Novel Without A Hero—presents an unrelentingly bleak assessment of society. The ending is unhappy, all of the characters flawed to varying degrees. It is significant that critics of the time chastised Thackeray for refusing to throw his audience crumbs of moral fiber.

The other comparison one might draw in examining the moral character of The Wire is the penny dreadful, Victorian booklets which exploited sensationalist drama, horror, and Gothic tradition. Penny dreadfuls were fiction published on pulp and could be purchased for a penny per pamphlet, often featuring monsters, vampires, highwaymen and crooks. Usually, these publications bear little similarity to the highbrow syndications of the time, their cliché down to an art form, their treatment of hackney topics procedural in nature.

By 1846, the time The Wire first began syndication, the Victorian audience was already familiar with an underworld of crime, the systems arrayed against it, the cop-and-robber story. But while only the penny dreadful exceeds The Wire in its depictions of violence, ugliness, and depravity of the world, these procedurals should be considered as a separate genre. They reached for the simple thrills of titillation. Meanwhile, The Wire had pretenses of social commentary, exposing deeper truths, persuading its readers not only to witness a corrupt society, but also to understand it.

Morality in Art was one of the most prevailing topics in both literary criticism and philosophy of Victorian times, propounded strongly by the art critic and philosopher, John Ruskin. Ruskin’s central argument was that one must reveal Truth in literature, but in doing so also reveal Beauty. One must present the moral beacon to which we all must aspire. One must not write without Hope. It is significant also that today, Thackeray is not charged with undue cynicism or depravity; rather, he is thought to be “sentimental, even cloying.”

Literature today is no longer concerned with morality the way it was in the nineteenth century. Unrelenting, bleak images of society are celebrated for their realism, as representations of humanity. And yet, we have very few images, representations, or new and challenging canon that captures the essential helplessness, the inevitable corruption, the deep-lying flaws of both society and humanity in the way The Wire does. Again, I would contend that such a feat could only be accomplished in the Victorian Age, through the serial format, which allowed for such layered complexity. In no other way could such a richly textured tapestry of a city be constructed from ground-level up. In no other way could the faults in the underlying foundations of society’s institutions be exposed. In no other way could our own society be held up for our examination, and found so sadly lacking.

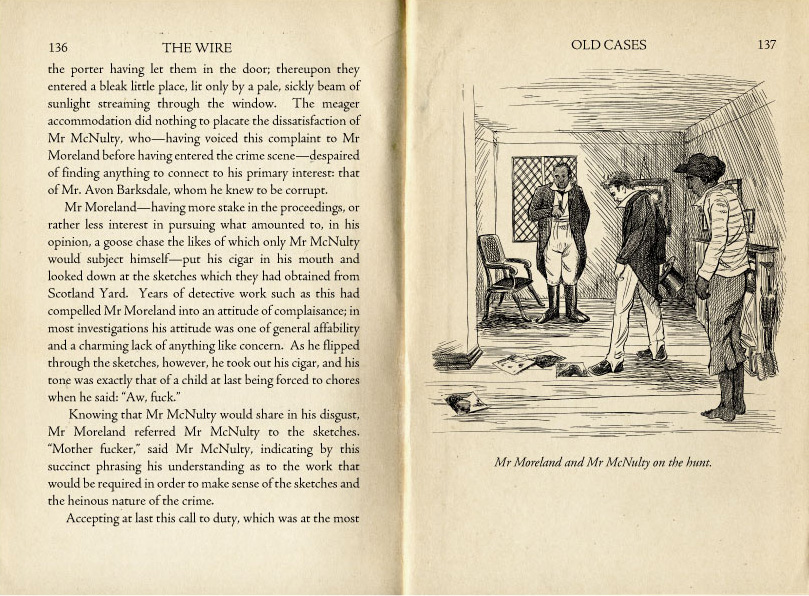

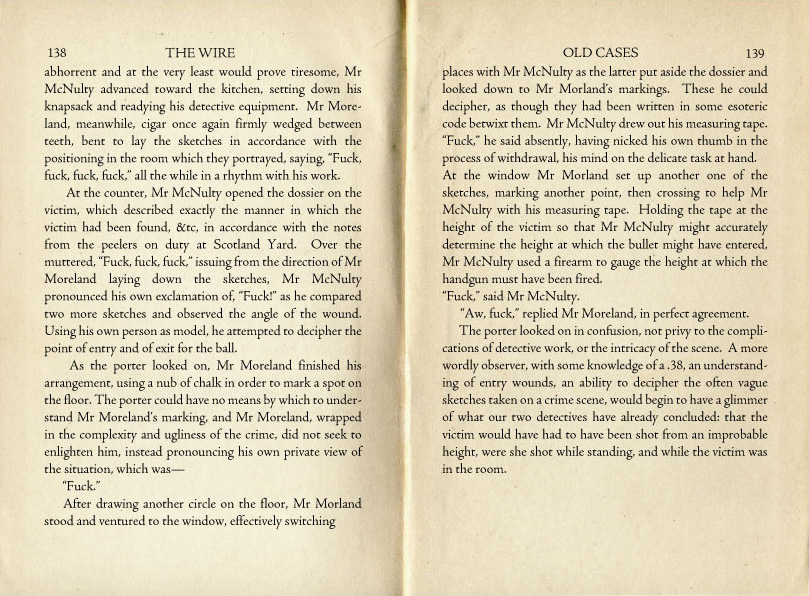

Yet this extraordinary feat of story-telling could not have been accomplished solely by Bucksley Ogden. It would be a mistake to say that one creator or author was responsible for The Wire, when the illustrations played such an essential role. Just as Sidney Paget immortalized Sherlock Holmes independently of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle by giving the detective his famous deerstalker cap and cape, so too did The Wire’s illustrator, “Bubz” contribute to The Wire.

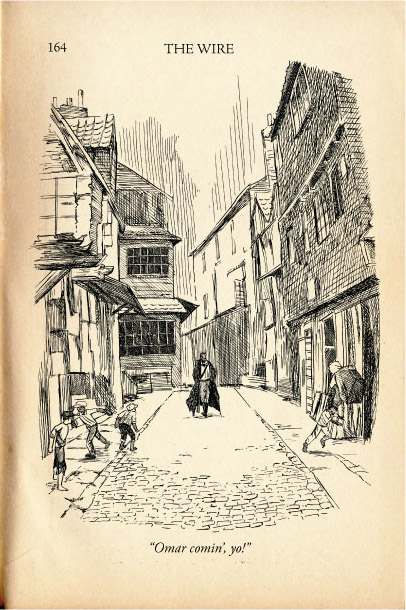

Would William “Bunk” Moreland be the same character without his cigar, ever-present but almost never mentioned? Would Avon Barksdale be as intimidating and yet beautiful, were Bubz not able to capture his panther-like movement, his violent grace? Could Joseph “Proposition Joe” Stewart be as memorable and endearing were he not the portly man we grew suspicious of, and somehow at last learned to love? Certainly Omar Little would not be Omar Little without his coat, like something out of the previous century; nor would he be Omar (“Omar comin’! It be Omar!”) without the weal running down his face, signifying past violence, a life of both heroic romance and mythic tragedy.

The illustrations are yet another essential element lacking from the story-telling of today. For one thing, we would not allow our cast to be represented by the “others” in our society Bubz renders so lovingly. Bubz gave us reality, and he made it beautiful. The standards of art today are no longer concerned with reality, while our fiction demands nothing but. Movies, television, the internet have all morphed our expectations, twisted and changed our visions, until we only wish to see Ruskin’s ideal: a pristine, white, purer version of ourselves.

In our age, we can never experience a modern equivalent of The Wire. We would be unwilling to portray the lower classes and criminal element with the patience or consideration of Horatio Bucksley Ogden or of Baxter “Bubz” Black. We would be unwilling to give a work like The Wire the kind of time and attention it deserves, which is why it has faded away, instead of being held up as the literary triumph it truly is. If popular culture does not open its eyes, works like The Wire will only continue their slow slide into obscurity.

Ms DeLyria and Mr Robinson are grateful to the Special Collections department of the University of Washington for generous access to their Ogden collection, including the two 1863 editions from which these illustrations were digitally scanned. Those wishing for access to more of “Bubz” Black’s illustrations may contact Mr Robinson at seanmichaelrobinson at gmail &c. Joy DeLyria can be contacted at joydelyria at gmail &c.

________

Update by Noah: The entire Wire Roundtable is here.

Update by Noah: A sort of sequel to this post is here.

Update by Noah: Joy and Sean have written an entire book about H.B. Ogden and the Wire, entitled Down in the Hole: the unWired World of H.B. Ogden— it’s out now.

Brilliant.

Sheer genius.

Pingback: Linkblogging for 23/03/11 « Sci-Ence! Justice Leak!

Ogden really was a genius- it’s a shame he’s not better known these days. I suppose his prose might be a little ponderous for a modern audience, but his plotting and understanding of social problems is really unparalleled.

I like the article too…but do you really think Ogden’s so quintessentially Victorian? I feel like there are lots of serialized narratives that deal with serious issues if you just look in the right place. Doestoevsky’s television dramas for example; I guess they’re less realistic than Ogden, but they definitely confront serious issues in a narrative way that’s pretty accessible, and arguably more morally complex.

I just don’t see why we have to bash the present in order to praise the past.

You know, every once in a while somebody will tell me that there’s television out there that’s actually worth watching- and I’m sorry, I just haven’t found it yet. It’s all car chases and gun fights, or some drippy domestic drama. I’ve hear of Doestoevsky before- I know a few of the series he worked on have been recommended to me a few times- but the economic realities of producing a televisions show really do make it impossible for an individual vision to make it to the screen. There just has to be too much compromise intervening along the way. So, this Doestoevsky guy was the series creator, maybe the head writer or show runner- that still means lots of other writers working in tandem, dozens of actors, hundreds of technicians, and a whole beaurocracy behind them to front the money, sending down orders on high for McDonalds product placement and other commercial considerations. No, I’m okay with remaining ignorant television.

I should note that, although I share her interests, Joy is the real scholar of the time period- I’m just an enthusiast. So hopefully she’ll be able to weigh in here, especially in regards to your Russian television serial comparisons.

I think it’s hard to watch “The Possessed” for example and think it’s not a very individual achievement. The acting style is just really bizarre, for example; it’s kind of bipolar melodrama, Trollope on meth. Not sure quite how he managed it, but it really looks like nothing else out there. (And that’s not even talking about the Christian themes….)

I’m pretty into that Henry James too. I guess you could say it’s drippy domestic drama in some sense — but I love the unabashed wordiness of it. Really, you wouldn’t believe that anyone could say sentences like that on television. You can’t even remember the beginning of them by the time you get to the end; the whole series is a fog of verbiage, with the characters looking more or less as confused as the audience.

We’re living in a golden age I tell you.

I do love that drawing of Omar, though. The Victorians did have some things on us.

Oh God, don’t even talk to me about Demons. Wasn’t Neitzsche on that show? I don’t understand why people keep talking about Charlie Sheen when that man is around. Talk about crazy. As for originality, Dostoevsky makes no secret of the fact that he stole the best material from the Overcoat production team. The only thing worthwhile Dostoevsky ever did was Notes On The Underground. He should’ve stuck to mini-series.

I do confess to having a weakness for Portrait of a Lady. But 1980s soaps always get me, no matter how weak and strung out the plot.

Imo the only great serial to grace the post-modern era was the 1970s manga, Les Miserables. Despite the cartoonishly drawn characters, I recognized in it the elements of a truly intricate serial plot.

I remember reading excerpts of the Wire in my 10th grade English textbook. The editors substituted “fudge” for every “fuck” and “American of African descent” for every “nigger.” It was a weird read.

You like Doestoevsky’s description of the London subway system? That really seemed like a waste of his talents to me. But to each their own I guess….

And Les Miserables? Good lord. Javert is such a dumbed-down retread of Rorschach in that Moore serial….

I’m surprised The Wire is even in text books; it’s so obscure. Down with censorship! Except when censoring The Simpsons, Southpark, and Huckleberry Finn. These shows were obviously meant for children, as they are about children. If our modern times had any decency, they would recognize that show such as these are essentially escapist in nature, have no social relevance, and thus should not be corrupting our youth with the filthy likes of Mark Twain.

And dude, if you’re going to bring Moore into it, you might as well say Milton’s Paradise Lost is a rip-off of the Bible, while you’re at it. Besides, Moore himself borrowed from oral tradition when he wrote that epic (do you really call an epic poem a serial?). In fact, if you ask me, Moore is just as much of a hack as Virgil was with the Aeneid: the were both borrowing from Homer. (Btw, have you seen the latest translation? Snyder argues the word that traditionally has been translated as “squid” is actually closer akin to “weapon”, or WMD in modern parlance. His translations are always wildly inaccurate, though interesting from a critical standpoint.)

I think it’s fair to call an epic poem a “serial” when it’s run as a series of broadsheets to be chanted in marathon relay sessions by costumed castrati, sure. I guess you could get all pedantic on me, but it’s a blog post comment section for Christ’s sake. Give me a break.

There’s borrowing and there’s borrowing. Moore took oral tradition and did something interesting with it. Hugo took Moore and made Javert. Nuff said.

To be fair to Dostoevsky, he was swallowed up and corrupted by the Hollywood treadmill after his documentary ‘Raskolnikov:Portrait of a Killer’ won the Golden Globes. Remember his doc series on HBO, ‘Gamblin”? He implicated himself in that shoot as directors never have before– ruining himself financially to get to the bottom of that disease.

Guess he sold out…

Next you’re going to be telling me Ranma can be considered a manga because it was performed in the 16th century by strangely androgynous men dressed as women with plots that revolved around cross-dressing and mistaken sexual identity. Pfffffffffft. Get real.

and may I also note that referring to a series of missives transmitted by telegraph as “blog post comments” is highly dismissive and devalues significant academic discourse STOP in the future all of these discussions will be performed over the modern bell telephone and literary criticism as we know it will cease to exist STOP value academia while it still lives for soon it shall only exist in a bubble of disassociated intelligentsia STOP

Does anyone remember those bizarre Pac-Man eppisodes that Stephen Crane wrote for “Saturday Supercade?” That was the most depressing cartoons series ever, at least after Thomas Hardy stopped working on “G.I. Joe.”

Wait no, Crane was “G.I. Joe,” Hardy was on the Globetrotters cartoon, and Poe wrote those really monotonous Transformers episodes. Those were some anxious robots.

Ugh, the hell with Zach Snyder… not only does he constantly favor flowery look-at-me phrasing at the expense of the text, his Moore translation seemed flatly ignorant the critical aspect of DIALOGUE with the oral tradition Noah mentions. Specifically, Moore’s liberal, detailed quotations from Steve Ditko are so bowdlerized as to render them mere surface decoration, despite being utterly fucking central to the work, down to seemingly tiny sections — Dr. Manhattan’s disastrous encounter with the scribes — referring directly to crucial verses from Ditko’s Captain Atom. And yes yes, the Kalermites will tell you that attribution is difficult in antiquity — where would our classics departments be without “Bob Kane”? — but Ditko, remember, commonly operated with an intent of conversion, to deliberately replace earlier, pagan narratives with substitutes derived from that unfashionable monotheistic bedrock, Mr. A, himself (of course!) parodied in the form of Rorschach, despite the protestations of “Sunday Catholics” with no appreciation of tradition, duly aided and abetted by Mr. Snyder… you see why I’m pissed??

Although, I’ll even read Snyder’s shitty-looking novel this weekend before I sit through one more second of Ayn Rand, the enduring (if limited) popularity of whom can only properly be analogized to the embrace of Tommy Wiseau among particular Victorians… contrary to one million posts online, I found it a relief when she just plopped that dude in front of the camera and had him talk, because she cannot frame a shot to save her life…!

I think Jog may win the thread.

Words fail me. As a fan of Victoriana and _The Wire_, I am in awe of your appraisals. Expect increased traffic, for I’m circulatinbg this far and wide.

Pingback: Indicating by this succinct phrasing his understanding as to the work that would be required in order to make sense of the sketches and the heinous nature of the crime. | Sinting Link

Oh, one pedantic point. Your book excerpt mentions “Scotland Yard” in a book published in 1846. The Metroplitan Police was less than twenty years old at that point: might want to check if the phrase “Scotland Yard” was used at the time.

Holy crap, you weren’t kidding about the increased traffic. Thank you, sir.

Mr. Siano,

It’s wonderful to meet another Ogden enthusiast! “Scotland Yard” was used in print to refer to the London police headquarters as early as 1830, a year after its founding, although it certainly would be possible that the text has been modified in the collected editions- Ogden himself oversaw the 1863 edition from which our excerpt was scanned, shortly before his untimely death. We don’t have access to the original magazine installments, so I’m unable to confirm whether this passage has been altered- but the term was definitely in use.

Pingback: Idea IS the format » “Mother fucker,” said Mr McNulty…

Pingback: Charles Dickens inspirerades av The Wire? « Niklas Elert

Outstanding, one of the best things I’ve seen online. My friends will enjoy it too.

This should be required reading in any college Victorian Novel class. Brilliant.

MattD-

It would be better, frankly, if Ogden were still available in print, so that people could enjoy him in the original versus our poor summation/appreciation. But thank you for your kind words regardless.

Thank you. Amazing.

Pingback: The Wire - The best TV show ever? - Page 18 - aberdeen-music

Pingback: The Wire as a 19th century novel. Omar comin! | The Strut

lol The Wire…Omar…McNulty…the scene on pages 138 and 139…lol

Pingback: Flavorwire » Reimagining ‘The Wire’ As a 19th Century Serialized Novel

The Wire is an incredibly intelligent and highly entertaining show that deserves the Dickens comparison. David Simon is a great storyteller, who has done something that American storytellers rarely do: he has looked at the underclass of society with both a sympathetic and critical eye, and has shown that these people have no chance of ever living the American Dream.

What is truly amazing is that Homicide, the first series that Simon worked on, is nearly as good as The Wire. Although it was made for network TV in the ’90s, and thus presented a somewhat sanitized vision of the world, the writing in that show often matches and sometimes exceeds the writing in The Wire. Tom Fontana, the show’s creative head, produced 7 powerful seasons that featured intelligent scripts, dynamic characters, and probably the best acting ever seen on TV.

We should be thankful that we are living in the age of David Simon. He and his team of collaborators — including Fontana, Ed Burns, George Pelecanos, Richard Price, Dennis Lehane, Eric Overmyer, among others — have produced incredible stories now for 15 years.

Pingback: Still bored? Read these links – 3/24/2011

Eli,

Do you mean David Simon, the Greek poet? I’m not sure who these other fellows are that you mention, but thank you for your interest.

Brilliant, but one typographical quibble: I cannot believe that “etcetera” was ever written “&tc” as shown. Since & is a typographic representation of “et” (latin: “and”), it should be written “&c”.

Alas, Mr Schmorg, the type-compositors of the day were all too often un-Christian rampsmen, ticket-of-leave desperados, and other drink-sodden counter-jumpers. And some were Irish, to boot.

Surely none can expect these Grub Street bloodsuckers to compose a perfect page for a mere penny dreadful (twopence coloured).

So totally brilliant that I want it to be perfect, so that it need not hang its head in any grove of academe. Which is why I mention that it’s “fey”, not “fay” and “bourgois” not “bourgoisie–when used as an adjective.

I know this sounds tediously picky, but I am serious about wanting it to be as perfect in the small ways as it already is in every way that counts. It should live forever in every Victorian literature class ever taught from here on out.

Judy:

“Which is why I mention that it’s “fey”, not “fay” and “bourgois” not “bourgoisie–when used as an adjective.”

Wrong on both counts, Madam.

‘Fay’ has been a variant of “fey” for centuries, as in ‘Morgan le Fay’.

And the adjective is not, as you so recklessly asseverate, ‘bourgois’, but ‘bourgeois’.

By Gad! Must we tolerate the invasion of bluestockings, these Amazons not content withtheir destiny in the home?

Next the hussies will demand the vote!

Love it, love it, love it. But I think it’s a mistake not to mention the clear influence Ogden’s work has on later serialists like Thomas Hardy, whose bleakness I always considered unique, but was obviously derivative of this earlier work. A few further observations – http://telephonoscope.com/2011/03/24/horatio-ogdens-the-wire/

I have always loved Ogden’s ‘The Wire’ and so I am very glad these writers are bringing attention to the masterpiece through their essay. I do wonder if any of you are familiar with my second favorite forgotten Victorian serial novel that I also consider an unknown masterpiece. It is called ‘Battleship Galatica,’ which concerns these 12 islands colonized by the Victorians where they use automata as laborers. At the beginning of the story the automata rise up in revolt and massacre most of the colonists, but some manage to leave on ships, including on a battleship called the H.M.S.Galactica. The rest of the novel involves the survivors’ adventures as they try to get back to England while being constantly attacked by the automata that are chasing them. It’s a great narrative with very meaningful meditations on the consequences of imperialism, industrialization, and the breakdown of the distinction between humanity and machinery (spolier alert: some of the surviving humans turn out to be automata, though they don’t realize it until much later). The work, possibly inspired by the writings of Samuel Butler, is a great answer to the pro-imperialist adventure tales of H. Rider Haggard. Anyone else aware of this great work, which I think is a close second the Ogden’s ‘The Wire’?

I can just see Borges writing a story about how Sean Michael’s critical essay gradually led to the intrusion of episodes of The Wire into actual current reality. Borges would have said that Ogden was a precursor of the pseudo-encyclopaedists of “Tlon Uqbar”.

I am giddy with pleasure. Thank you —

I’m glad to see Bucklesby Ogden get his due at last, and I must commend your research skills–I’ve never seen these illustrations before, and your uncovering of them is nothing less than superb. However, I can’t help but argue that Bucklesby Ogden’s melding of the serialized novel with greater societal concerns owes something to the earlier work of W. “Weed” Jossun. True, Jossun worked in the tradition (some would argue ‘ripped off’) Shelley & Stoker, but he managed to meld a concern for the lives of juveniles with a host of traditionally disrespected genres–the Gothic novel, the horror novel, the penny-dreadful, and yes, whatever genre you choose to put Sir Alan Moore in.

I would be very curious to hear your thoughts on the British publisher of “The Wire,” particularly given their decision to stick with Bucklesby despite the lack of profitability;

in addition, I hear they did similarly good work with a couple of earlier serials, including a rumored American Western–though I’m having a devil of a time tracking it down.

Even the comments section is in on the conceit. Well-staged and an interesting take on the series, worthy of a classroom. Well-said.

Sirruh[s]–I BEG you!!! George Pelecanos is “the Greek poet.”

I love this! You made my day!

Fantastic! Hugely grateful to you both for unearthing a long-underappreciated classic. Is there much hope for you scanning more of Bucklesby Ogden’s work, to make it more widely avaialble to those of us without your resources and education?

LOL Horatio Bucklesby Ogden HBO

Pingback: The Wire Finally Achieves Its Goal of Becoming a Dickensian Novel

Pingback: Polpette: l’inutilità della puntualità (e i gelati, letteralmente) « Grazia Magazine Blogs

Pingback: “The Wire” as a 19th Century Serialized Novel | clusterflock

Please make a poster of that ‘Omar comin, yo!’ sketch. I will buy it.

As an english major and a fan of The Wire, this has to be one of the smartest, most well-thought and hilarious essays I have read in a good long while.

Pingback: Wire from the Victorian era « Lavonardo

I’d have to beg to differ with Eli. The serial Mr. Ogden created a decade before The Wire wasn’t bad per se, aside from some terribly obvious writing that occurred from time to time. Unfortunately, the greedy penny pinching publisher he was working for kept revising his prose to the point where even readers could detect the compromises at play. The troubles reached their bizarre apex when the central female character was written out halfway through the serial’s run.

Luckily, Ogden later on was able to find a more amenable publisher, resulting in his much lauded recent masterpiece….

I think this is my favorite blog post I’ve ever read. What did critics like Ruskin think of Ogden’s later work, Generation Kill and Treme?

I enjoyed the essay but find the Bodymore reference insulting. Simon did not intend to insult Baltimore. Baltimore is what it is and he portrayed that, but most of us, including Simon (a resident), still take pride in Charm City. The Wire is not about the setting. So why take a cheap shot at my city? Baltymore or Balt-more or anything else would have been more appropriate instead of perpetuating a stereotype. http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/opinion/bs-ed-the-wire-20110124,0,6777732.story

Pingback: nerdbastards.com | A Re-examination of The Wire as if it Were ae Victorian Novl

Pingback: Linkage: 26/3/11 | Moore Than This

I worship at your alter.

Pingback: The Wire, the Victorian novel « it's a small web

Genius! Horatio Bucklesby Ogden…LOL :-) The Wire, IMHO, was one of the BEST shows on HBO or TV, period.

Fantabulous! Thank you!

Bravo! If only Dickens were alive today, perhaps he would have to come clean on the sources for his inspirations and plot devices.

I was glad to find this essay, but I was a little surprised to find so little reference to how Ogden challenged the social and sexual mores of the time. Both Lady Greggs, whose knowledge of the opium trade was invaluable to the investigations, and Beadie Russell, who monitored the docks for signs of vice, were strongly implied to be unofficially in the pay of Bodymore police, making them quasi-professional police. More than that, both Greggs, with her female “close companion and long-time house guest”, and Omar, who mourns for “Brandon, more than a business associate in his illicit business, but a friend of the most intimate order”, are almost certainly gay. Perfectly fine now, but awfully racy back then. Actually, legend has it Oscar Wilde–he was the screenwriter for The Importance of Being Earnest and won the Oscar in ’96 for it–spent most of his last days reading Ogden’s work before he finally succumbing to meningitis. Considering Wilde’s prior legal troubles, one suspects he picked up on the subtext.

Also, does anyone else remember a rumour that The Wire would be turned into a television series? This would have been nine or ten years ago now. I think they were going to change to time frame to the modern day. It sounded awful, frankly, and it’s good nothing came from it, but still.

Dr. Veritassium,

Thank you for your illuminating comments. The proclivities and private activities of Lady Greggs and Omar alike have indeed provided much discussion re: their interpretation. As for the alleged television remake, I heard such rumors as well, but they seemed completely out of the realm of possibility to me. Please see my above comments re: television in general.

Pingback: Ratchet: What If The Wire Were A Victorian Novel? | Air Conditioning by Jay Fingers

Jaylyn, you’re right that David Simon loves Baltimore. He has called “The Wire” a love letter to the city. But “Bodymore” and “Murdaland” are used in the show itself. So I’m not sure that your criticism is fair.

Also…the Baltimore Sun is falling over themselves in enthusiasm about the post. Not that they’re the be all and end all of Baltimoriana or anything (David Simon forbid!), but it suggests that at least some Baltimore folks don’t find the usage especially offensive.

Great essay. Why not throw a copy of The Wire up on gutenberg.org with all the rest of the classics there, since it looks like you have it already scanned it into electronic form. Thanks in advance.

Pingback: The Wire tonight BBC - Page 18 - The Liverpool Way

Can you advise, where can I get a copy of this book. Hope Google Books make them available soon. I couldn’t find in Amazon or Google Books.

Well, as Sean and Joy note, Ogden’s been criminally (if that’s the word I want) ignored. No modern editions, and yes, even Project Gutenberg doesn’t have an edition up. I don’t even think there’s a Wikipedia page. I think this may be the first consideration of his work on the web, though I’m sure there are scholarly articles.

This post has gotten a lot of attention, though, so maybe if we’re lucky more of his work will be available in the near future.

I heard Google’s scanning machine completely destroyed one of the few extant copies. It didn’t even get halfway through.

The #@&!¤£!ing BBC…?

Whoa I had never heard of this…so interesting! Let the research begin for an elusive copy…;-)

Pingback: Perpendicular Universe - 03/28/2011

Aren’t we forgetting that Dostoevsky wrote and directed the best film of the past 20 years: “O Brother, Where Art Karamazov”?

I swim laps at UC Berkeley, so sometimes I talk to undergrads in the locker room. UC Berkeley offers for-credit courses that study The Wire. As literature, storytelling, sociology, anthropology.

I am not in on the joke here. One of the writers of this article, sean, weighed in and said he doesn’t know who David Simon is, maintaining the puzzling pose. I think that goes too far. Maybe I am stupid. My IQ, after all, has never tested above 185, but I don’t understand why sean would keep up the pose in the comments. I think I get the main point: that The Wire is great literary art, a reflection of our culture and every bit as worthy of academic and cultural respect as Charles Dickens. I might go further and posit that The Wire is better art. Lots about Dickens work bugs me.

Pingback: The Wire Unplugged (or should that be “wireless”?) « Eagles on Pogo Sticks

Pingback: Hit List: March 28, 2011 | IMDb: All the Latest

This is awesome guys, thanks! I have forwarded it to the official fan page.

Pingback: The Wire reimmaginato come un romanzo del ’900 | BadTv.it

I have not had the pleasure of this read. But I assure you my appetite is sufficiently whet to rush out, find a copy and barricade myself indoors and read it fornt to back!

:-)

This is really funny, but also a great critical examination of ‘The Wire’. This is one of the best articles I’ve read lately. Kudos sir!

Pingback: In Which I Use This Space To Share Cool But Ultimately Unrelated Links | Stetson's Pub Quiz

Is any of The Wire currently in print or available as pdf?

Pingback: The Wire as Dickens | St. Eutychus

Pingback: LanceTurner.com – The Design of David Fincher: Tuesday’s Good Reads

Pingback: All The News That’s Fit to Link

Pingback: “When It’s Not Your Turn”: The Quintessentially Victorian Vision of Ogden’s “The Wire” « The World According to GAG

as an English major, congratulations on elevating the art of TV criticism. if this was in the New Yorker, you’d get a Pullitzer

Well, the New Yorker linked it…does that count?

The Talk of the Town: We called on dapper, bespectacled Noah Berlatsky last week to get the latest on…

Ugh! Noooooooooo§

Pingback: Columbus, OH: "You can't pushblock the Devil, man."

This is simply fantastic. Thank you!

Pingback: The 100 Best Quotes from The Wire Jammed into One Video and See The Wire Converted into 19th Cen. Literature | Nonpopulist.com

Pingback: The New Yorker: In the News: Cookbook Bibles, Chekhov vs. Star Jones | Books in Media

WOW! Omar scene is great!

Pingback: Fake Historicity: ‘The Wire’ as Dickensian Serial «

Pingback: Unreality - The Wire as 19th Century Literature |

Pingback: "The Wire" Reimagined As A Dickens Novel | News One

Simply. Amazing. And. Refreshing.

Pingback: Absolutely brilliant, must-read post for every fan of The Wire | Saint Petersblog

Pingback: HBO’s The Wire as Victorian Era Literature « LatinRapper.com Blogs

Pingback: An Odd Homage « Back Of Town

Pingback: Odd Words « Odd Bits of Life in New Orleans

This shit is priceless, not just the article but the illustrations of the “original work.”

Pingback: Omar Comin’, Yo. « Calamity Blog

Someone needs to make a print of that “Victorian Omar”…put it on canvas…I’d buy it and put it in my living room. This is easily the most fun I’ve had reading anything this month. Great little “critical review.”

Pingback: “Aw, fuck,” replied Mr Moreland, in perfect agreement | Poison Your Mind

Pingback: Sort-of memes that are cracking you up at the moment - Page 367 - London Fixed-gear and Single-speed

Where can I buy this book!!!

fuuuck!

Pingback: Indextwo | A Victorian Vision of The Wire

Pingback: links for 2011-04-11 | The 'K' is not silent

Pingback: Does This Tumblr Page Make Me Look Smart? Infinite Snark and The Decline of Western Civilization | So Fake It's Real

Pingback: The Art of Darkness » Blog Archive » The Link Dump and Sixpence

Kudos. Methinks you win the Internet.

Pingback: What the hell am I doing here? I don’t belong here. Woah oh. [sustain] | We are Now Go.

Pingback: Roundup – Fan-Made Film Credits Better Than Actual Credits « The Heat Death Hour

Pingback: Moral Seriousness as Detail Orientation « Disaster Notes

Pingback: John Nack on Adobe : (rt) Illustration: Buscemi eyes, Ali, & more

Pingback: Twitter Weekly Updates for 2011-04-01 | Mark Englehart Evans

Pingback: Friday Free-for-All: March 25 | Crisis Magazine

Pingback: Picaros everywhere! | Profesora Bordner's Blog

Pingback: The Wire – zaboravljena viktorijanska novela « Tipfeler… Backspace!

Pingback: All the pieces matter: analysis, essays, and anything else on The Wire « ReadJack.com

Pingback: The Wire – Abrumaciones y meta-T

What was facinating about reading The Wire was not so much reading about the characters but the character architypes. While It is almost impossible to think of these characters as cliches, the fact remains that almost all of these characters are at one point or another replaced with another. When Kima is transferred as a homicide detective, is she not simply replacing McNulty who has abandoned the post (this made more poinient through Kima’s neglect of her personal life)? Has Carver not redeemed himself as more than simply a West-Division head-knocker and taken the path of moral righteousness that ‘Bunny’ had instilled (even despite ‘Bunny’s’ expectations)? More obviously, Omar appears to have been replaced by Mike (both able trigger-men familiar with violence and an assumed checkered past) and ‘Bubbles’ by ‘Dookie’ (both men of former prosperity dragged to the depths of despair and addiction). The only man who is not explicitly replaced is Marlo and while the reader is left with a strong intuition that Marlo cannot live a ‘straight life,’ no replacement figure emmerges to take control his his dominion. In a bleak sense, this particular archetype being laid to rest is the closest message of hope Ogden can provide; seeming to reassure the reader that all the pain, struggle, suffering and devotion might have accomplished at least some small thing other than merely shuffling players.

Pingback: What comics could learn from The Wire Tastes Like Comics - Tastes Like Comics

Pingback: Schizoid.Us - Memories And Possibilities Are Ever More Hideous Than Realities » Blog Archive » “When It’s Not Your Turn”

Pingback: Baby Got Books » The Novel as HBO

Pingback: ‘The Wire’ circa 1846. | Ratking.info

Pingback: The Wire : The Dickensian Aspect | Can't Shut Up About

Pingback: Rooty-Tooty Snark-and-Snooty « Joshua Unruh

Thank you for this post. Just amazing. Now I can really use the word “Dickensian” :)

Pingback: The Wire as Victorian Lit « Beerblaster dot com

Pingback: This Is Not Your Father’s Oldsmobile « Back Of Town

Pingback: March 2011

Pingback: Onwards and Upwards | Accidental Jellyfish

Pingback: Charles Dickens x The Wire | Just Another Waitress

Pingback: “The Novel Just Skated Past” | Full Stop

Pingback: From Film to Word: ‘The Wire’ Reimagined as a Dickensian Classic « Word and Film : The Intersection of Books, Movies, and Television

Pingback: Weekend Links: What’s Your Blues Name? - Cine Sopaipleto » Cine Sopaipleto

Pingback: Weekend Links: What’s Your Blues Name? - Sopaipleto » Sopaipleto

would really like to second the request for a poster-size Omar Comin’ Yo sketch

Pingback: Way Down in the Hole: 6 Great Dramas That Owe a Debt to “The Wire” | SPH - Small penis humiliation

Pingback: Dickensian Meta-satire : The Honeycomb

Pingback: Live “Wire” « Humor in America

Pingback: Vendredifférent: Hommage à The Wire « Le Blog du Studio SPG – Montréal Québec

I think I’m going to cry.

Pingback: I’m Not Crazy!- Somebody Else Thinks American Liberalism is Victorian | Deconstructing Leftism

No pingback from Salon? They do link to this post, though.

http://www.salon.com/2012/09/13/the_wire_is_not_like_dickens/

Pingback: Another Week Ends: Dead Liberal Arts, Glorious Ruin, Cagematch: Hoffman-Phoenix, Victorians in Baltimore, Creative Anxiety, and Imputed Guilt (by Association) | Mockingbird

Pingback: Vendredifférent: Hommage à The Wire | Le Blog du Studio SPG – Montréal Québec

Pingback: Dickens Day 2012: Dickens and Popular Culture « Dr Charlotte Mathieson

Pingback: I’ve Got a Fever, and the Only Prescription is More Moonstone: Addiction, Reading, and “Detective-Fever” in Serial Narratives | Points: The Blog of the Alcohol and Drugs History Society

Pingback: The Wire by H.B.Ogden « American Television From Broadcast Networks to the Internet

Pingback: Mixed messages | Hal O’Brien

Pingback: Watch Andrea Bargnani Take One Of The Dumbest Shots In Basketball History

Pingback: Anatomy of a Binge: Orange is the New Black | One Day, One Thing More

Pingback: Quick Project Update | Shelf Control

Pingback: Keep the devil down in the hole | more stars than in the heavens

very good !

Pingback: Vaga Fertur Avis

Just finished Down in the Hole — absolutely brilliant. When are you going to publish the five volume set? Even as a publish-on-demand, there is a niche of people who would buy this– and I am just one of them.

Hey David!

Thanks very much for the kind words. If you have a few minutes, feel free to post a review on your website of choice. For low-profile books like DITH, reviews really do move copies!

As for other volumes, both Joy and I are pretty wrapped up in other projects at the moment. We also worked really hard not to place DITH into retelling/full-on adaptation territory, which I think a full 5-volume set would definitely do. I’m not saying it’s impossible– only unlikely at the moment. Thank you very much though for your kind words and enthusiasm!

one of my new favorite blogs, We Who Are About To Die, I find this great treatment of The Wire as Victorian serial. An amazing level of detail and dozens of hours of work went into this. I’m still only one [ – See more at: https://www.hoodedutilitarian.com/2011/03/when-its-not-your-turn-the-quintessentially-victorian-vision-of-ogdens-the-wire/#sthash.RojgMFQx.dpuf